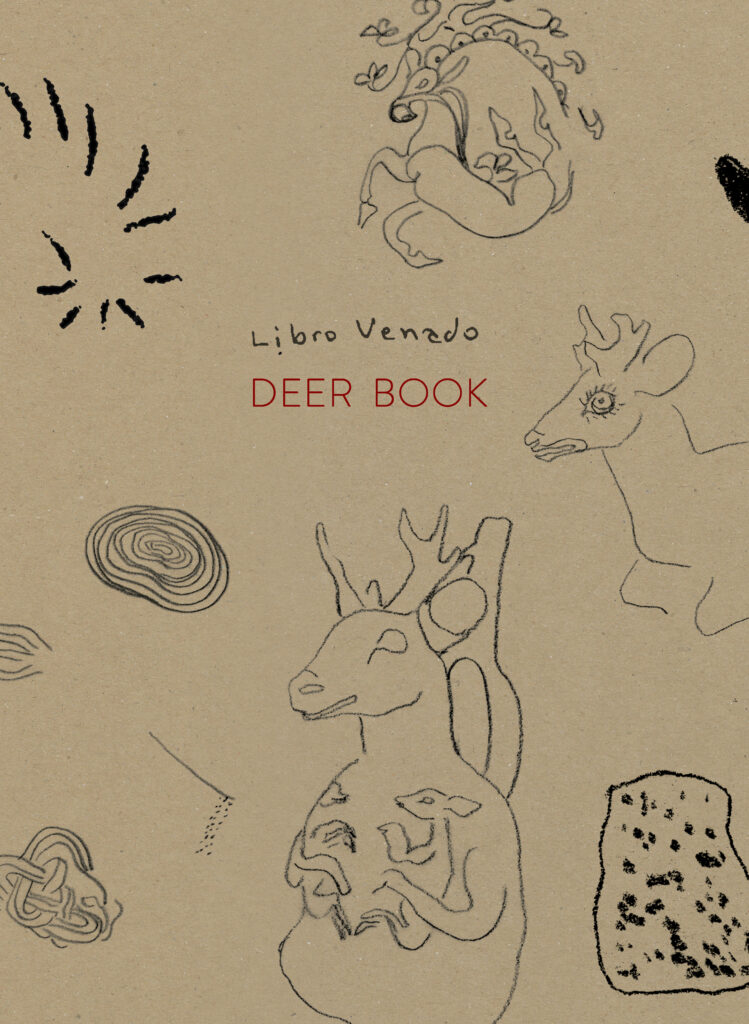

Cecilia Vicuña’s Libro Venado Deer Book, like the creature named in its title, hides with great

beauty in plain sight. The hardback publication looks like a schoolbook with an old-fashioned

jacket made from what recalls a brown grocery-store paper bag. On the front and back covers,

pictographic, pencil-like drawings of deer and fawns, branches and various undecipherable

shapes outlined in light gray. At an angle, when exposed to the sun, for instance, these embossed

elements refract light just enough to create a subtle phosphorescence, as if they had been etched

into a rock or carved into a hide.

At the front of the book, in lieu of a contents page, thick bright yellow pages present a

handwritten, five-page, fold-out “map of the book.” This has, in keeping with the rest of the

volume itself, no page numbers. It nonetheless offers a top-to-bottom trajectory that corresponds

somewhat dreamily to what’s inside the Deer Book. A triad of rectangles, for instance, contains

evidence of Vicuña poetically thinking, ostensibly directionally, but not exactly referencing the

book’s contents:

Tra-

what is the tra- of trans?

_____

Deer theorizes

theory looks at us

_____

Breath flower

I am the flower

The map ends with the handwritten Vicuña-ism of “Ack now ledge ments,” maybe indicating

that the artist is on the verge, or ledge, of something immediately, now.

Vicuña was born 1946 in Chile, and left in 1975 due to the military invasion by Augusto

Pinochet. Nearly fifty years later, while living between Santiago and New York, in Deer Book

she muses over words such as tran-ce, trans-formación, trans-curso, trans-norte, and trans-

ducción by drawing them out like the petals of a flower. For Vicuña, words such as these possess

marvelous and mischievous properties not to be commandeered by dictionaries or absolute

meaning, but as evidence that things—like herself—go about, touched by companions and

encounters, with no permanent or dominant manifestation.

The actual acknowledgments in the book propose three ways Deer Book came to be: The point in

time when Vicuña and her husband visited Pecos, Texas in 2004 to study 4,000-year-old rock

paintings of a deer/jaguar ritual dance, or in 1985 when Vicuña either translated or was translated

by the 15 Flower World Variations, the Deer Dance of the Yaquis by Jerome Rothenburg; or

perhaps when Vicuña was a child and first understood that the whales of Isla Mocha in the south

of Chile transport the dead to their “true abode on the other side of death,” and then later came to

understand that whales descend from small deer.

Some of the pages in Deer Book have reproductions of handwritten words and drawings. Four

full pages, for instance, contain six words and appear as though handwritten in pencil: “la ve

nada” and “ve la nada” (“nothing sees her” and “sees the nothing”) lowercased and not

translated. Vicuña, rather than making sense, engages with existential conundrums as to whether

seeing and existence are intertwined; whether seeing nothing is something that can be done—or

perhaps coming upon a realization of the actual absence of everything because it has been seen?

Mind-altering Latin-American substances mentioned repeatedly in the book—such as peyote and

mescal—may shed some light on such semiabstract enigmas, and the possibility that questions

contain their own answers. As Vicuña points out—whether to clarify or confuse—near the

beginning of the book, “In Amerindian poetry, the living world and song depend one upon the

other.”

The interior sections of Deer Book, include poetry, photographs, and drawings that cumulatively

have more a sense than a subject—not unlike a walk in the woods. Deer Book, like its title,

contains words in both Spanish and English throughout. It doesn’t, however, have one language

converted seamlessly into the other as a traditional translation. This being the case—and to that

effect makes even more engaging—despite the fact that, in its first five pages, three real-life

translators are the first of several translators given credit throughout the book: Daniel Borutzky

(poet and translator), Jerome Rothenberg (poet and translator), and James O’Hearn (poet,

translator, and Vicuña’s husband).

Earthy, ephemeral-looking, elegant papers of different stocks, textures, and hues that mimic

dramatic elements of nature are interwoven throughout the volume. Sun yellow, fall-leaf orange,

cloud gray, water dusky blue, and dirt multitoned brown come to mind on these colorful pages

which are as sumptuous to touch as they are to look at. Vagaries of slickness and coarseness, in

fact, recall Vicuña’s best-known large-scale sculptural works with textiles: cords with knots in

the Incan quipu style of keeping track of taxes and taking censuses. This quipu style, which also

happens to be quite pretty, was banned by Spanish conquistadores. Vicuña has famously created

almanacs of more personal things with her own quipus, such as menstrual cycles, hanging

monumentally in museum galleries.

Other pages have been printed as though by an old typewriter in a pleasantly readable

monospaced slab serif font in black, white, brown, or red ink. Occasionally pages in this book

have nothing at all on them, lending the Deer Book a sense of a sketchbook not yet filled. Single

pages of orange or beige vellum are interspersed throughout the volume as well. These are

overlaid with Vicuña’s photographs or drawings, providing a partial view to each side of the

page. This creates a forest-like sensation of peering around one tree to see what’s on the other

side, prompting philosophical questions about whether there’s really any “here” or

“there,” when there are many “heres” and “theres” necessarily coexisting everywhere, and not

just because or when they’re seen.

Through the veins of a photographed tree leaf printed in black on taupe vellum, for instance, a

red drawing emerges that conjures a deer, falling water, branches, and that comprises more hand-

drawn leaves on its verso. A new section begins from here—possibly a chapter—titled “El yo del

sonido/The I of Sound” that includes two short poems by other poets that embrace the essential

antithesis of Vicuña’s project, which she seems more interested in joining than owning

(despite the fact that her name alone is on the book’s spine):

No se ha visto a ningún yo

No one has seen an I

—Macedonio Fernandez

Los espiritus no son “convocados” para utilizarlos

Son la sustancia del yo

The spirits are not “summoned” to be used:

They are the substance of the I

—Pierre Clastres

Vicuña intertwines the elusive nature of the “I” with the book’s ethereal structure, inviting

readers to lose themselves in its pages as they would in the depths of a forest. Here, the “I” is not

a singular point, but a constellation of experiences and visions, ever shifting like the light

refracted on its cover.

Sarah Valdez is former manager of publications for the Guggenheim Museum, and a senior editor at the New Museum in New York. Her writing has appeared in Art in America, ARTnews, Interview, and Flash Art, among numerous other publications.