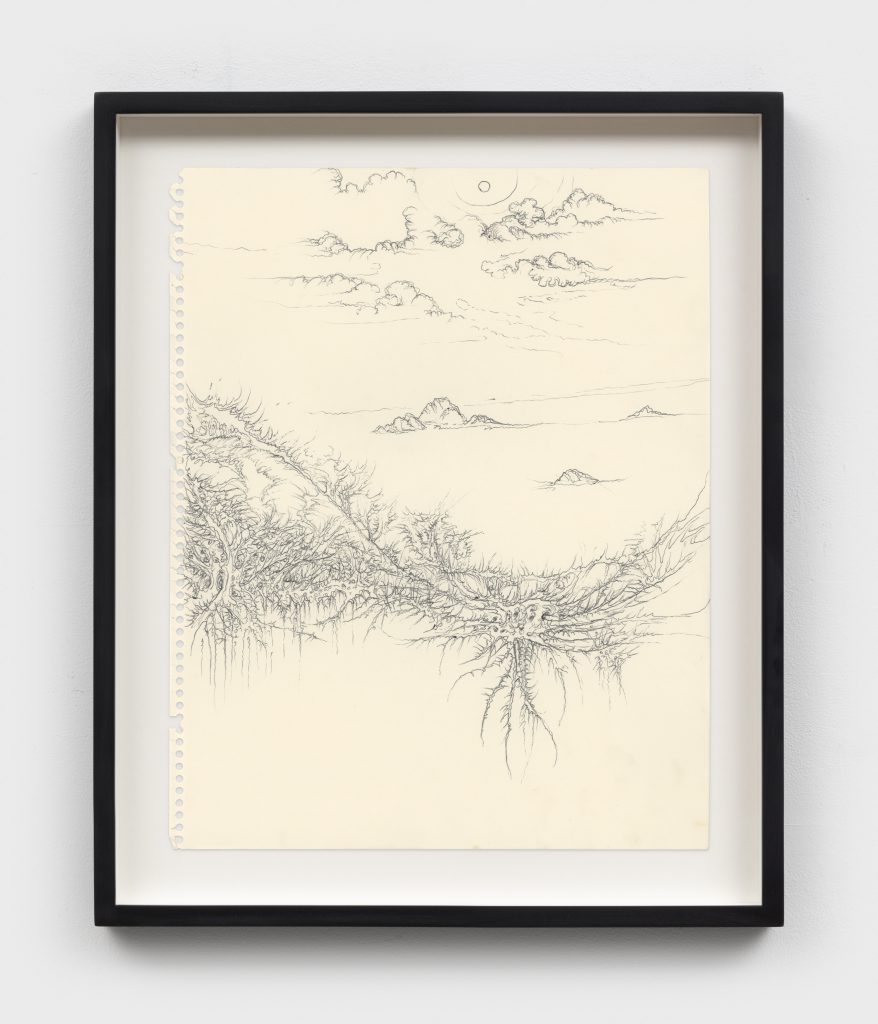

Martin Wong and Paul P.: The Midnight Sea, A Little Dash of LSD juxtaposes the art of two queer artists working decades apart. A close look at the pieces, generally pencil or ink sketches, suggests a lack of expectation that they would ever be displayed in a gallery. Many of Wong’s drawings bear evidence of the damage of being ripped out of a spiral notebook: they are on lined paper, not sketchpads, with discolored or frayed edges. Most of them date from the early to mid-seventies, when he learned to draw by sketching people on the streets. P.’s work, with sparse backgrounds and use of colored pencil, resembles small studies. Both artists depict figures and landscapes, and their shared subject matter can make it difficult to differentiate between the artists. The absence of wall text compounds this fusion, leaving viewers to guess which artist drew which piece.

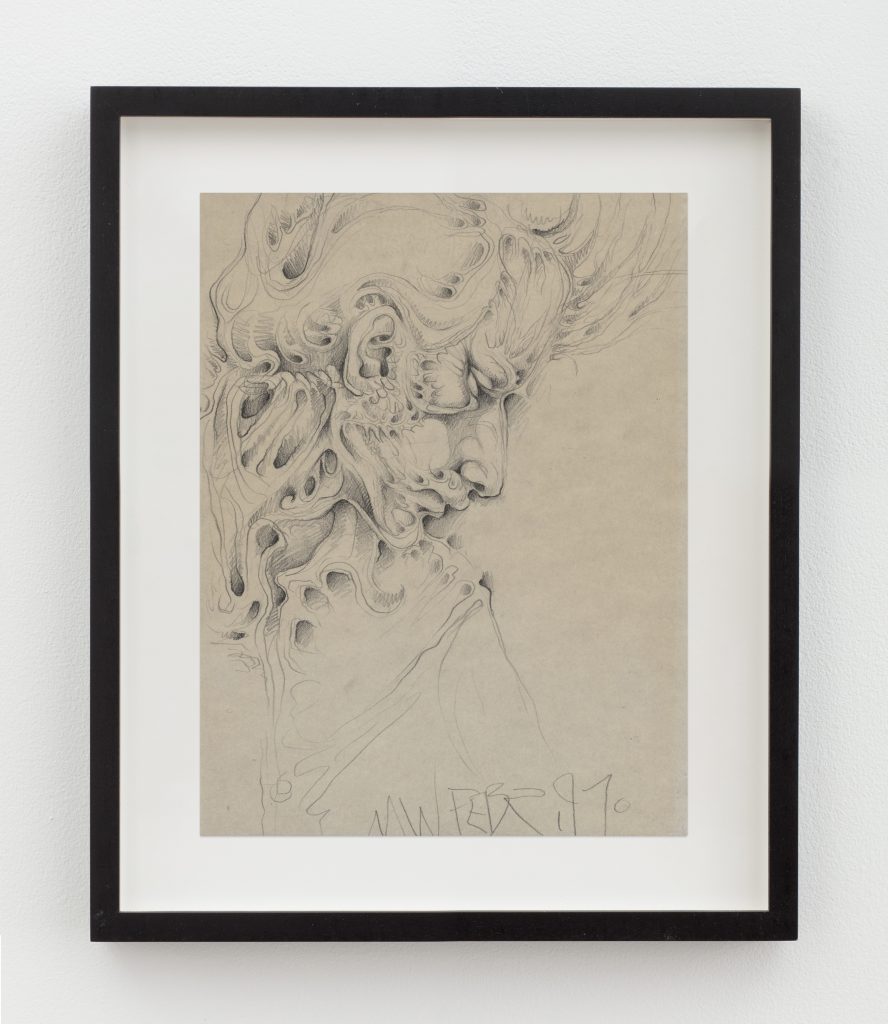

Ultimately, Wong’s work shines through. His sketches convey a raw, chaotic energy with their layered lines, lending each piece a sense of vibration. In contrast with Paul P.’s more controlled approach, Wong’s work stands out for its messy yet vigorous aesthetic. This stylistic contrast is particularly evident in pieces like Wong’s Gregory (1972). In the portrait, Gregory’s hands are sinewy, and the ribbed, dotted clothing he wears evokes the patterns of a peacock’s feathered eyespots. In Wong’s Untitled (Tom Mueller in profile) (1970), the subject’s skin resembles knotted wood. Untitled (Landscape) (c. 1970–72), though it borrows techniques from traditional Chinese painting, continues his themes of earthy chaos. The serpentine landscape—recurring in several of his drawings—suggests an overgrown slime mold: those irregular, intricate, amoeba-like collections of cells reaching across space. It also calls to mind viruses spreading through the ground.

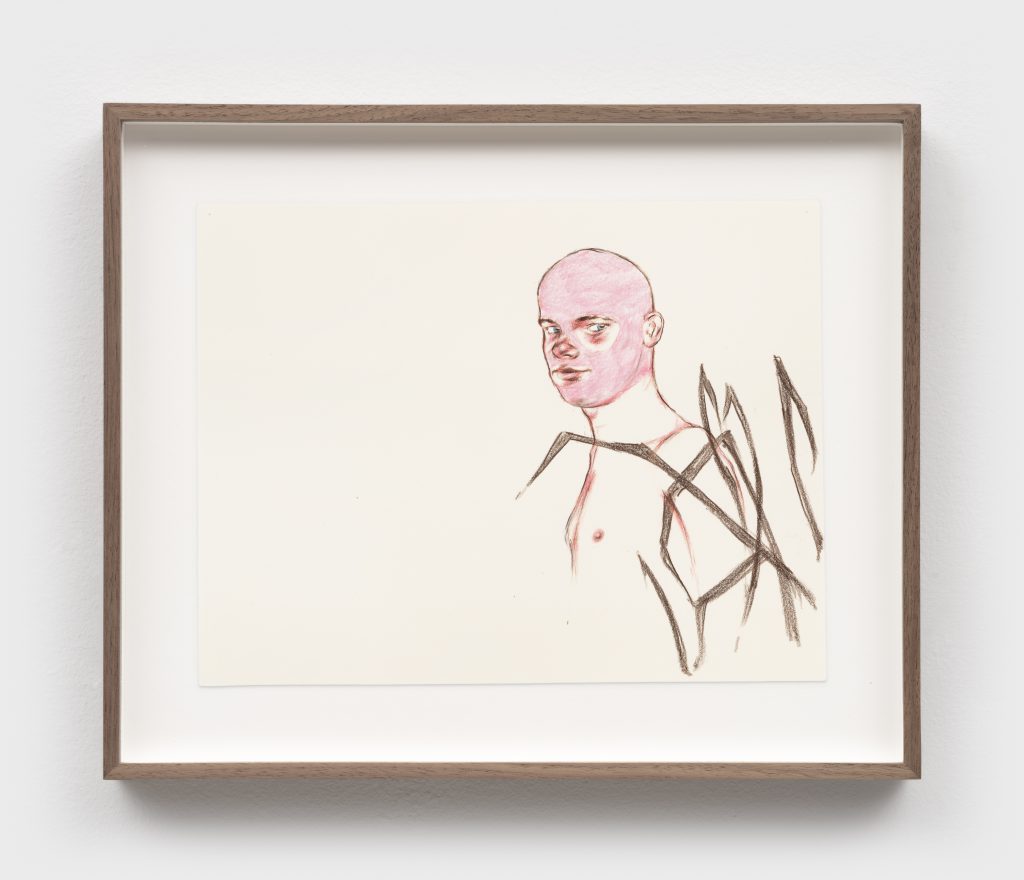

P.’s work is much more subdued. He drew a number of male figures—all based on the models found in gay erotic magazines from the 1960s through the ’80s. In Untitled (2001), a bare-chested man stands behind what might be branches, the top half of his torso outlined beneath a colored-in, pink face. The selective color leaves the man looking ill, particularly as it surrounds red under-eye bags. Untitled (2011) depicts a man walking on the beach, facing away from the shore, his head down in contemplation. None of his portraits depict more than one person; all of his figures stand in solitude.

Born in 1977, P. grew up in the aftermath of the AIDS epidemic, and his work serves as a tribute to the men who either watched swaths of their friends disappear or fell ill themselves. Wong himself died in 1999 to complications from AIDS, while P. continues to work as an artist, sourcing many of his models from the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archive. As I navigated the gallery’s multiple rooms, the significance of juxtaposing these two artists became clear. Seeing their work side by side, it is easy to recognize on the one hand Wong’s influence on Paul P., and on the other, how our fleeting encounters with strangers—in magazines, on the streets—leave a mark decades later.

This exhibition is organized by P·P·O·W Gallery, where it is on view from March 15 to April 27, 2024.