Below is a selection of some of the most memorable New York City art exhibitions of the season. The list contains museum as well as gallery shows, most of which are currently on view, and not to be missed.

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

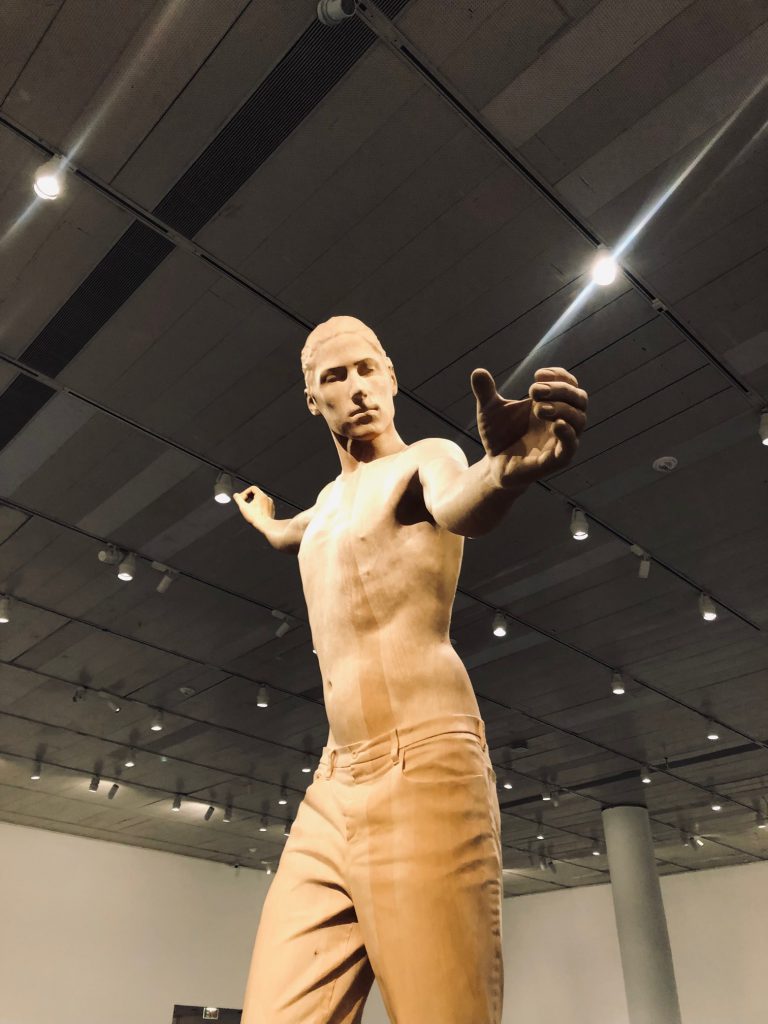

1.) Charles Ray at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 5th Ave, through June 5.

This remarkable survey of works by Chicago-born, Los Angeles-based sculptor Charles Ray, 69, contains only nineteen pieces from every period in his nine-decade career. Each of them commands the surrounding space in such a formidable way that an addition to the show would almost certainly have precipitated a feeling of overcrowding. On view in the exhibition, organized by the Met’s Kelly Baum and Brinda Kumar, are mostly figurative sculptures, plus several photos, and a kinetic wall piece—a spinning white disk nearly invisibly recessed into a white wall.

Photo: David Ebony.

Although the spacious rooms that the exhibition occupies at first seem light and airy, the material density and visual intensity of the individual works convey an unexpected sense of immeasurable gravity. Thematically, the works are enigmatic and ambiguous. Stainless steel pieces, such as the oversize nude duo Huck and Jim (2014) and the elegiac Sarah Williams (2021), address scenes from Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, and some of the racial conundrums therein.

The showstopper here, Archangel (2021), is a towering figure—more than thirteen feet high—made of carved cypress. Ray’s subject is Gabriel, now among the roster of the heavenly messenger’s many art-historical precedents. Initially, Ray’s angelic model held a sword; here, presented unarmed and shirtless, in jeans and flip-flops, Archangel comes across as a powerful but more down-to earth intermediary—delivering to those who listen a hopeful message for our times.

Courtesy New Museum. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2022.

2.) Faith Ringgold at the New Museum, 235 Bowery, through June 5.

In contrast to Charles Ray’s exhibition concurrently on view at the Met, Faith Ringgold’s engaging retrospective at the New Museum is jam-packed, and full of color and visual excitement. Raised in New York in the midst of the Great Depression, but immersed in the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance, Ringgold studied painting, and explored many other avenues of artistic and personal expression—from quilting to installation and performance art. Now 91, she has been known since the 1960s for incorporating crucial sociopolitical messages into her works, such as the “American People” series, which addresses the struggles of African Americans to overcome oppression.

In a composition such as American People Series #15: Hide Little Children (1966), Ringgold demonstrates her painterly acumen by creating a rather lyrical image with a poignant theme—a verdant nature setting that could serve as camouflage—faces enmeshed in foliage, almost as flowers, to protect the young from prey and all other unseen threats. Among many other highlights in the exhibition—organized by the New Museum’s Massimiliano Gioni—is The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro (1975-89), an elaborate installation that was used in a 1976 multimedia performance piece, with two standing female figures in mourning, and abstract wall-hung paintings with patterns of geometric shapes inspired by Congolese designs. The work, and a number of others by Ringgold of the period, evoke urban tragedy and a triumphant rebirth in the midst of the Civil Rights movement.

3.) The Hare with Amber Eyes at The Jewish Museum, 1109 5th Ave (at E 92nd St), through May 15.

As one among the legions of admirers of artist and writer Edmund de Waal’s hybrid memoir and historical treatise, The Hare with the Amber Eyes, I was thrilled to learn that the Jewish Museum would mount an art show inspired by this unforgettable book—an exhibition which would be designed by starchitects Diller Scofidio & Renfro, no less. Both the book and the exhibition follow the plight of the once powerful Ephrussi family (de Waal’s Jewish relatives), Ukrainian immigrants from Odessa, who settled in Paris and later in Vienna. It’s a particularly relevant story for today in the midst of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the late 19th century, the family established a vast banking empire, and collected Impressionist paintings as well as Japanese art, including some 264 diminutive netsuke sculptures, many of which are included in the exhibition.

The netsukes, now in de Waal’s personal collection, include several versions of The Hare with the Amber Eyes displayed in a number of vitrines throughout the show. The sculptures—tiny carved wood, bone, horn or lacquer figures and animals—serve as connecting links across great expanses of space and time—from the late 1800s in Ukraine to Tokyo and London today—just as they did in the book. Paintings by Manet, Renoir, and Gustave Moreau add to the visual appeal of period rooms reimagined for the show. De Waal reading passages of the book on a video monitor and audio tracks accessible via free headsets help to convey the collection’s history and survival.

In the foreground: Recumbent hare with raised forepaw, signed Masatoshi

Ivory, eyes inlaid in amber colored buffalo horn

Osaka, Japan, ca. 1880.

The show could be a bit challenging, if not confusing, for visitors unfamiliar with the book. However, as an adventurous experiment in creating a coalition of literature, visual art, and global history, the exhibition may prove to be unique—and therefore not to be missed.

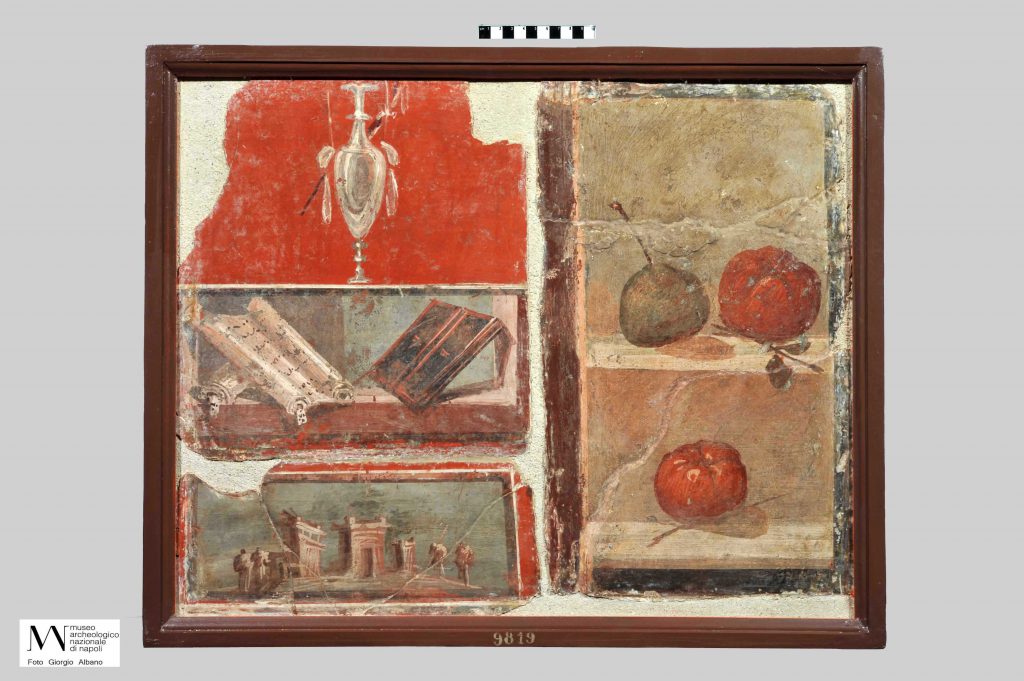

4.) Pompeii in Color, at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW),15 East 84th St., through May 29.

Rarely seen outside of Italy, paintings on loan from the National Archaeological Museum of Naples are at the core of Pompeii in Color: The Life of Roman Painting, a stunning exhibition organized by ISAW associate director and curator Clare Fitzgerald. These first-century CE masterpieces, taken from the walls of various Pompeii villas, offer not only a glimpse of life in antiquity, but also an up-close and in-depth look at the technical sophistication and compositional brilliance of ancient Roman painting.

Herculaneum, National Archaeological Museum of Naples: MANN 9819

Image © Photographic Archive, National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Subtle nuances of color and texture enliven each of these frescoed panels, which collectively encompass a wide range of themes, including comic theatricality, as in the resplendent Hercules and Omphale. Here, the Queen of Lydia glares disapprovingly at the inebriated mythological hero as she dons his lionskin cloak and wields his club. Elsewhere, multiple perspectives in the rendering of deep space enhance the charm of the ancient landscapes and still lifes on view, such as Still-life fragments representing vase, scrolls, landscape, and fruit, that contain examples of both genres.

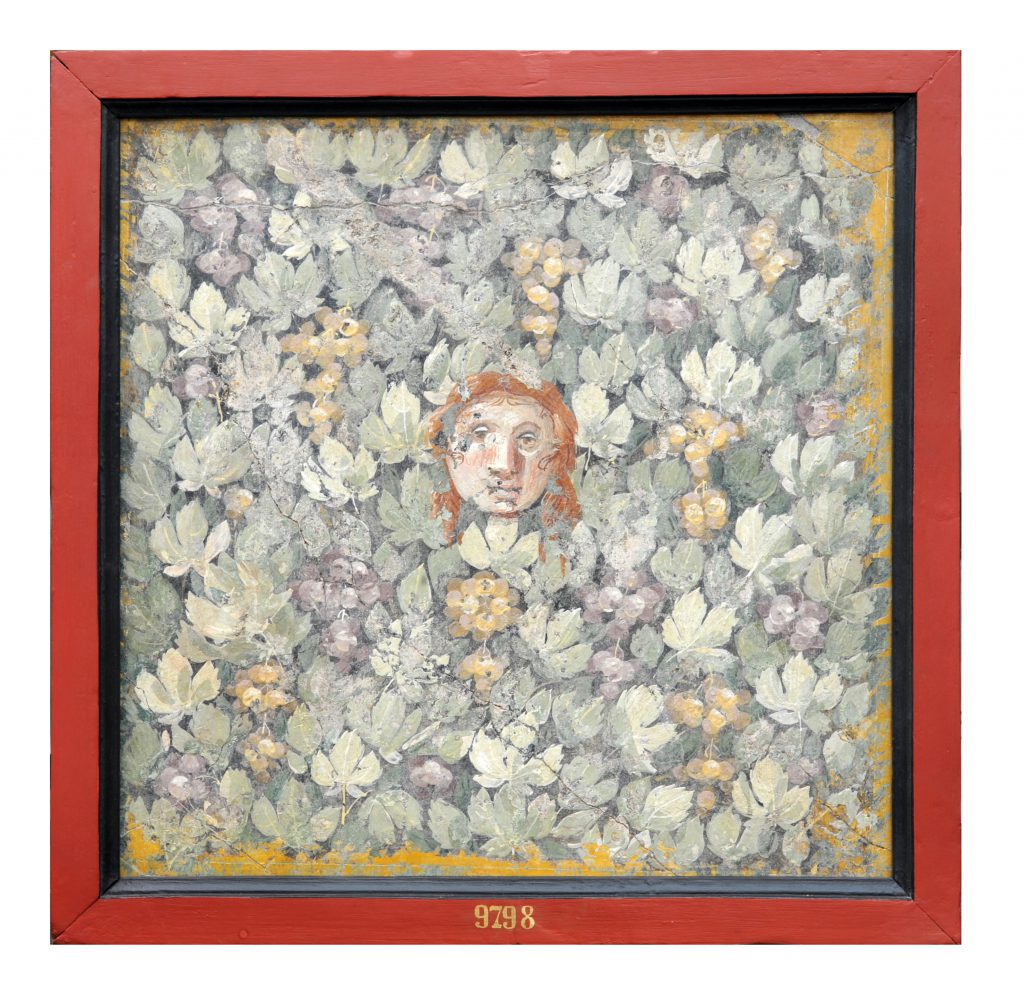

House of V. Popidius or House of Mosaic Doves, triclinium 13, east wall, central section, Pompeii, H. 54.6 cm; W. 55.2 cm

National Archaeological Museum of Naples: MANN 9798

Image © Photographic Archive, National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Another memorable work is the enigmatic Mask amid bunches of grapes and vines, which, according to most scholars, reflects the real garden surrounding a villa, as well as the face of its proprietor.

5.) Jean-Michel Basquiat at Nahmad Contemporary, 980 Madison Ave., through June 11.

Since his death in 1988 at the age of 27, Jean-Michel Basquiat has become something of a mythological figure. Often, regrettably, all the art-world hype and astronomical prices garnered by some of his works distract and distort his true accomplishments. Jean-Michel Basquiat: Art and Objecthood, curated by scholar Dieter Buchhart, goes a long way to rectify matters. The exhibition is a tightly orchestrated overview of the gritty street-smart works that brought Basquiat’s early New York notoriety to fore and eventual international renown.

Photo: Courtesy Nahmad Contemporary / Artwork © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

On view are early pieces painted on found materials, such as the plucky Untitled (Self-Portrait -The King), from 1981. Here, a reductive yet bold stick figure “king” collaged onto an etched mirror heralds the lofty ambition and raw energy that Basquiat would impart to the world through his art during his brief career. Nuanced personal statements with texts, such as the luminous Untitled (1960 Yellow Door), of 1985, demonstrate the poetic aims of his work, with the rough-hewn letters of “milagro”—“miracle” in Spanish—suggesting a prayer of transcendence.

Photo: Courtesy Nahmad Contemporary / Artwork © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Coinciding with the Buchhart’s exhibition, Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure, organized and curated by the artist’s family, features personal items from the artist’s estate, and several of Basquiat’s early and unusual experiments with Christian iconography, such as Crisis X (1982), with its cruciform shape and schematic rendering of a crucified figure; this work hangs above the silvery, three-panel Gravestone (1987), with a yellow crucifix at left. Created the year before Basquiat’s death, this work appears as a stark memorial tribute to a person or persons unknown.

6.) Zak Kitnick at CLEARING, 396 Johnson Ave, Brooklyn, NY, through May 8.

The calculable aspects of the unpredictable phenomenon of weather and climate change inspired Los Angeles-born New York artist Zak Kitnick, 38, to create this handsome exhibition, The Weather. The warm, glowing medium of neon—in red, yellow, blue and green—in looping and geometric configurations of tubing nestled within wall-hung shallow relief boxes, is the means of expression Kitnick chose to describe global air currents and the passage of time through the four seasons: spring, summer autumn, and winter.

The neon works suggest the constantly shifting weather conditions for air travel, just as Kitnick’s sculptures—reductive polished wood constructions in four geometric segments, capped with four shallow brushed-aluminum vessels—evoke the bowls that all travelers or visitors are obliged to deposit: cellphones, keys, wallet, or watches at airport check-ins and for other security clearances in airports around the globe. The first work encountered upon entering the gallery, A Year in Review (2021), serves as a kind of blueprint or floor plan for the overall structure of the individual pieces in the exhibition, and the show itself. It is a vibrant work with four circular forms counterbalancing a square, rectangle, and three other geometric shapes in neon representing all of the works on view.

Kitnick uses the language of minimalism, and serial art, but manages to maintain his own quirky individuality and idealism through the show. With these light-filled neon pieces, and airy sculptural vessels, the artist invites viewers to adapt to or slowly accept an idiosyncratic geometric logic and language that might help us to navigate or at least better understand the alarming prospects of climate change.

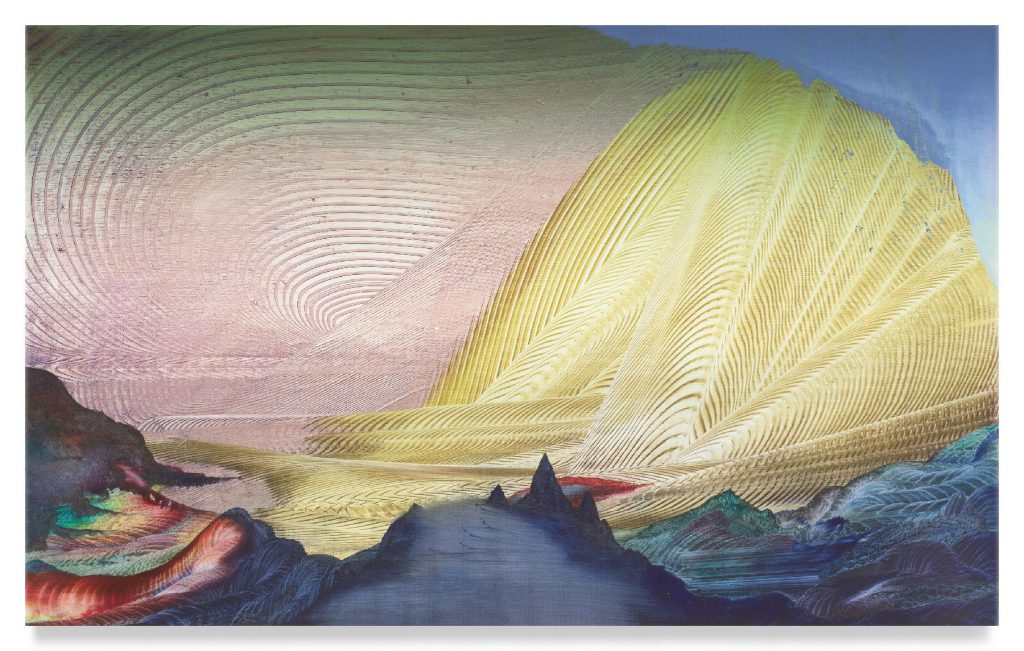

7.) Elliott Green at Miles McEnery, 525 West 22nd St., through April 23.

The hallucinogenic, quasi-illusionistic landscapes/dreamscapes that Elliott Green introduced in his work several years ago have reached their apotheosis in this dazzling show of mostly large-scale paintings. A Detroit native who lives and works in upstate New York, in the mid-Hudson Valley, Green uses various comb-like tools to achieve the moiré effects, and the sensation of undulating surfaces, air currents, and rhymical structures that is a prominent attribute of his recent work.

Many of the paintings here are epic in scale and thematic range, hinting at issues of climate change and the fragility of nature. One outstanding example, Ballistic Mist (2021), depicts a rocky landscape at left surrounded by billowing waves of a turbulent sea in the foreground. A blue mushroom cloud at far right soars into the sky, morphing with an exploding gray mass at center right in the far distance to threaten this would-be island paradise.

8.) Bill Carroll and Ron Milewicz at Elizabeth Harris Gallery, 529 West 20th St. through May 28.

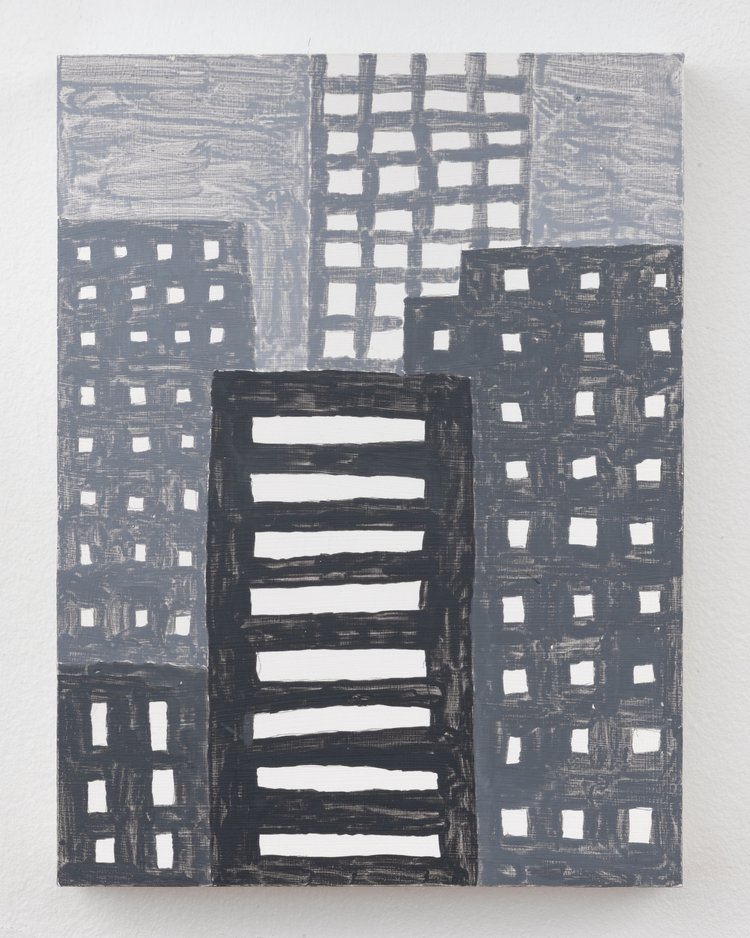

These two engaging solo shows could have been aptly titled “Town and Country” in their contrast of urban and rural themes. William Carroll’s “dawn and dusk” is a series of intimate, rather melancholy, cityscapes painted in translucent grisaille, with architectural elements rendered in terms of reductive simplicity, as in City 4 (2022), which approaches pure abstraction.

A number of works, such as City 10 (2022) recall Georgia O’Keeffe’s moody paintings of skyscrapers. Carroll, though, conveys the meditative quality of the relatively vacant city at the times of day—dawn and dusk—when the New York artist routinely explores the town on foot. He presents an orderly and idealized urban vision as an antidote to the typical chaos of New York City living.

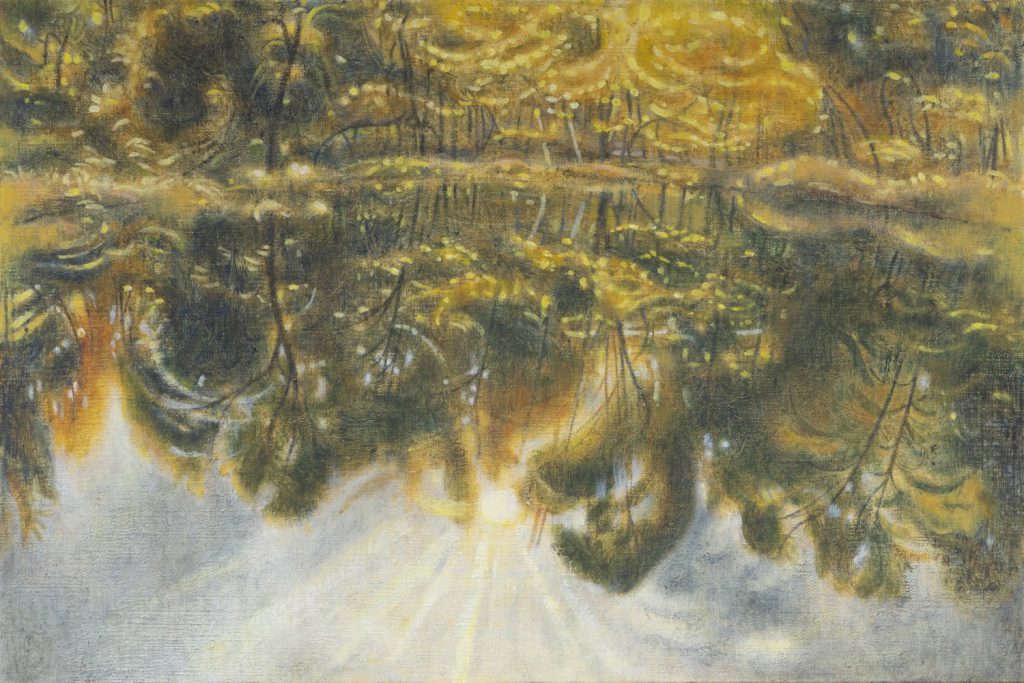

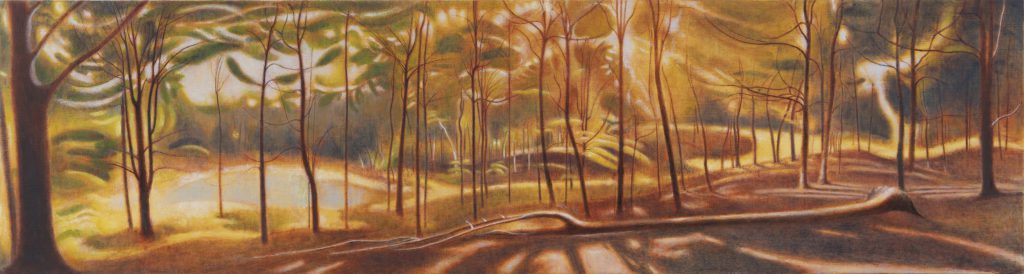

Known early in his career for his refined cityscapes, in recent years Ron Milewicz has focused on the transcendental possibilities of landscape painting—especially since the New York artist now spends part of the year in rural upstate New York. Most of the recent works in this show, A Meaning Made of Trees, are very modest in scale; several, however, including At the Edge of the Woods (2022), feature remarkably detailed, panoramic views of an undulating, luminescent forest.

The suggestion of divine light in the sun’s rays that permeate the forest corresponds to works by Samuel Palmer, one of the artist’s favorites from the Romantic period in 19th-century Britain. There’s nothing nostalgic about Milewicz’s painting, however. Another mesmerizing view, Reflections in the Pond (2022) is a rather disorienting image at first, until the viewer realizes that most of what initially appeared to be a forest itself is in fact its reflection. Contrasting with and complimenting Carroll’s serene and subdued urban views, Milewicz underscores the often tempestuous mutability of nature.

9.) Jennifer Wynne Reeves at Hutchinson Modern, 47 East 64th St., through May 6.

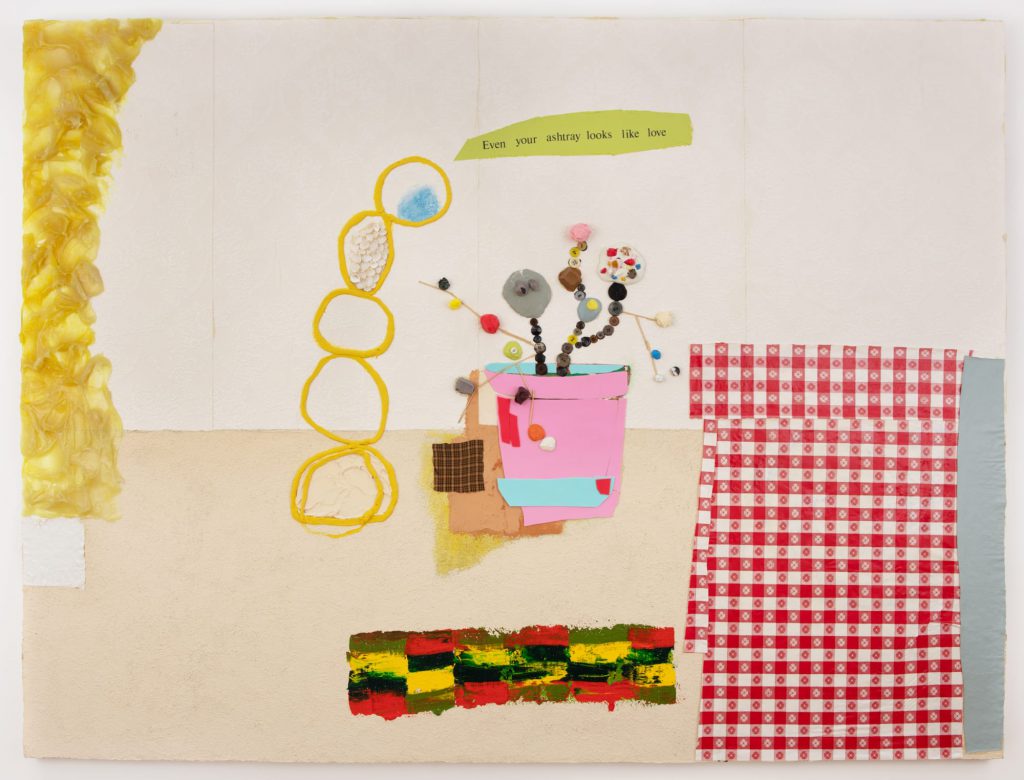

This compact survey offers a rare opportunity to explore the works of Jennifer Wynne Reeves (1963–2014), who many regard as one of the most talented painters of her generation. The Michigan-born, New York painter’s career was tragically cut short by brain cancer, but she left behind a stunning range of imaginative and robust paintings, works on paper, and photographic pieces. Trained as a musician, Reeves imparts a musical quality to all of her two-dimensional works, and sometimes provides lyrics, as in the whimsical Your Ashtray (2014), a large painting with collage that indicates a domestic interior scene, with a potted plant and a red-and-white tablecloth; it is one of the highlights of the show.

Photo courtesy Hutchinson Modern.

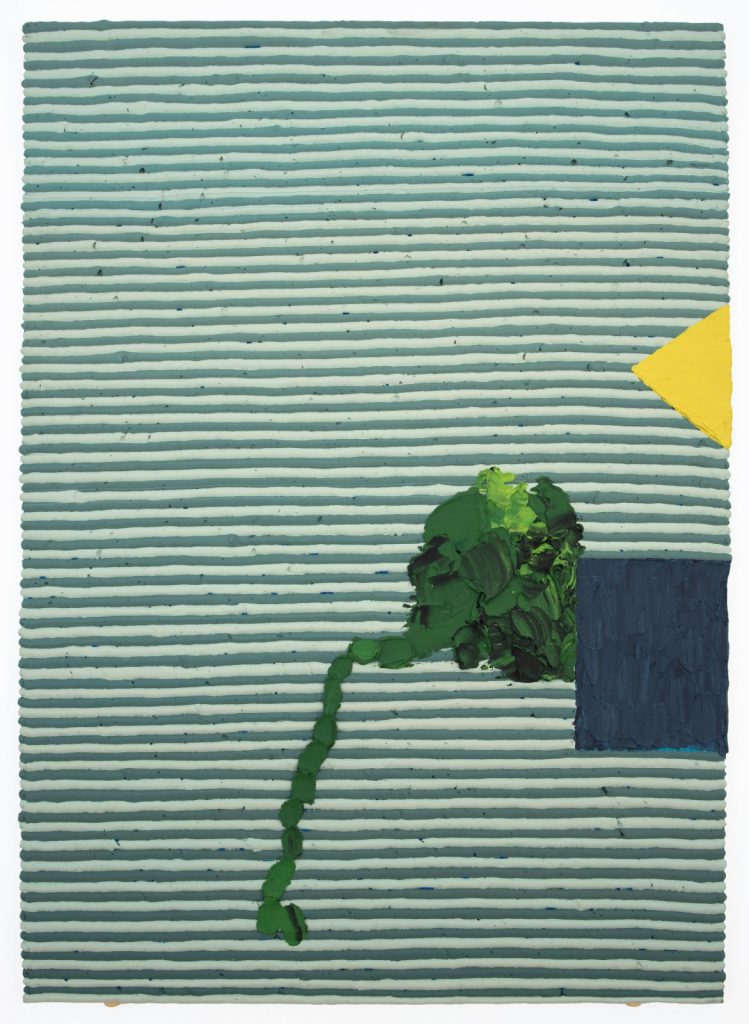

Reeves’s use of text is akin to cartoon bubbles here, and in other paintings in the show, titled The Line Talked Back. Her quirky merger of text and image corresponds to those of likeminded artists such as David Lynch and Jon Pylypchuk. Some of Reeves’s best works are wordless and purely abstract, such as the richly textured Initial Impulse: Blue Square Dreams of Salt (1999), in which a blue rectangle and yellow triangle at left against a striated background of green and blue play counterpoint to dense smudges of forest green that meander down the center of the composition in an unruly strand, like a furtive, leafy vine.

Nancy Grossman, G.I.O., 1969 leather, wood, paint, epoxy, horn, and metal hardware, 17 1/4 x 11 x 7 1/4 inches (43.8 x 27.9 x 18.4 cm).

Photos courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.

10.) Nancy Grossman at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, 100 Eleventh Ave. (at 19th St.), through May 27.

Nancy Grossman: My Body is a poignant and timely survey of the veteran artist (born in 1940) best known for her eerie, life-size sculptural heads covered in black leather, studs, zippers, and other accoutrements. Grossman has stated in interviews that she regards these pieces as self-portraits, intended to highlight the feminist taking-up of protective gear or armor against the threat of male aggression.” When she introduced these works in the late 1960s, such as G.I.O. (1969)—among the highlights of the show—they were often associated with S&M, especially apropos of the pre-AIDS gay leather scene.

Photo courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.

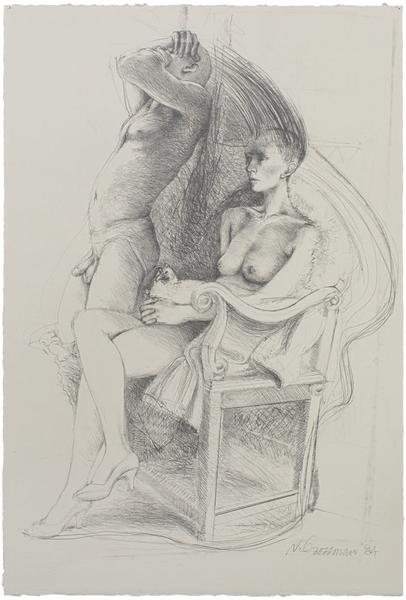

These self-portraits, as well as her long-running series of “gun-heads,” in which the human head morphs into a gun, such as Gun Head (1975), were also viewed at the time as a bitter protest of the Vietnam War; they are still resonant today as powerful statements against war and all forms of gun violence. It is also gratifying to see in this show several examples of Grossman’s relatively mellow pieces, such as the graceful drawing Two Figures with Chicken (1984), in which her technical gifts as a consummate draftsman are readily apparent. ●

Text © David Ebony 2022

Yes, David Ebony is my adored and long time friend but the brilliance and poetry of his writing, and the depth and breadth of his knowledge still generate joy ,wonder and admiration. Thank you David for your independence and for sharing your love of art.

Great selection! Ron m was my very first drawing teacher back in 1998, love him and his work

I have seen about half of these. After reading your texts I am out the door to see the others. Thanks, David, for these concise pieces on these shows!

This is such a diverse group of art and artists and your insightful commentary is a pleasure to read. I had only a vague awareness of Jennifer Wynne Reeves and this presentation led me to research this remarkable artist. Thank you David!

Thank you, David, for your beautiful writing and thoughtful engagement with art!