Artists wrestle with the state of and effects of the Information Age at Kunsthalle Basel

Owens, Untitled [SMS +41 79 807 86 34], 2021 (back). Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

In 1970, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York showed Information, a group exhibition inspired by the beginning of what has now been termed the Information Age. Marked by the new and ever-increasing ability for people to access information easily through the rise of the internet, computing power, and other technological advancements, artists in the exhibition toyed with various interpretations of how information could be approached and utilized—for better or worse. Hans Haacke showed his seminal MoMA Poll, a landmark piece within the tradition of institutional critique that polled visitors asking if they approved of Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s attitude toward the Vietnam War; and John Giorno provided four telephones in the gallery for visitors to call local numbers to hear a poem recited (a work that incited the FBI to surveil the exhibition). Fifty years after the close of this exhibition, the Kunsthalle Basel presents INFORMATION (Today), a thought-provoking exhibition that is a (loose) response and thematic continuation of the historic MoMA exhibition.

Curated by the Kunsthalle’s director and chief curator Elena Filipovic, the show hosts an international roster of artists, many of whom are already well known for their work in the digital and technological art realms. The exhibition, however, does not immediately convey its premise; rather than being laden with only black-and-white documents and documentation or high-tech gear, the show is materially diverse, and spans a breadth of mediums, from sculptural installation to painting and video. Additionally, the individual galleries are not inherently organized (or categorized, rather) by certain topics or themes, and, instead, each artist’s contribution is an independent, artistically personal interpretation of a certain facet of technology or information relay today.

The exhibition opens with French-born artist Marguerite Humeau’s Riddles (Jaws) (2017–2021), a series of chrome barriers, or what could be mistaken as truncated banisters. Humeau refers to the barricade at the front as the “Mother Sphynx,” and the ones behind it as “Vertebra,” revealing the artist’s research into ancient mythology. Mounted on each piece, there is a blue “eye,” a round light replete with a loading icon pupil. The steel gates are reminiscent of crowd control and security guardrails, like the kind commonly seen in airports, public venues, or even detention centers, controlling the flow of people and restricting access. The barriers are internally networked together, and they sporadically make a clicking or banging noise, which is often echoed by another barrier, triggered by visitors’ movements via radio signals.

Photo: Philipp Hänger/Kunsthalle Basel

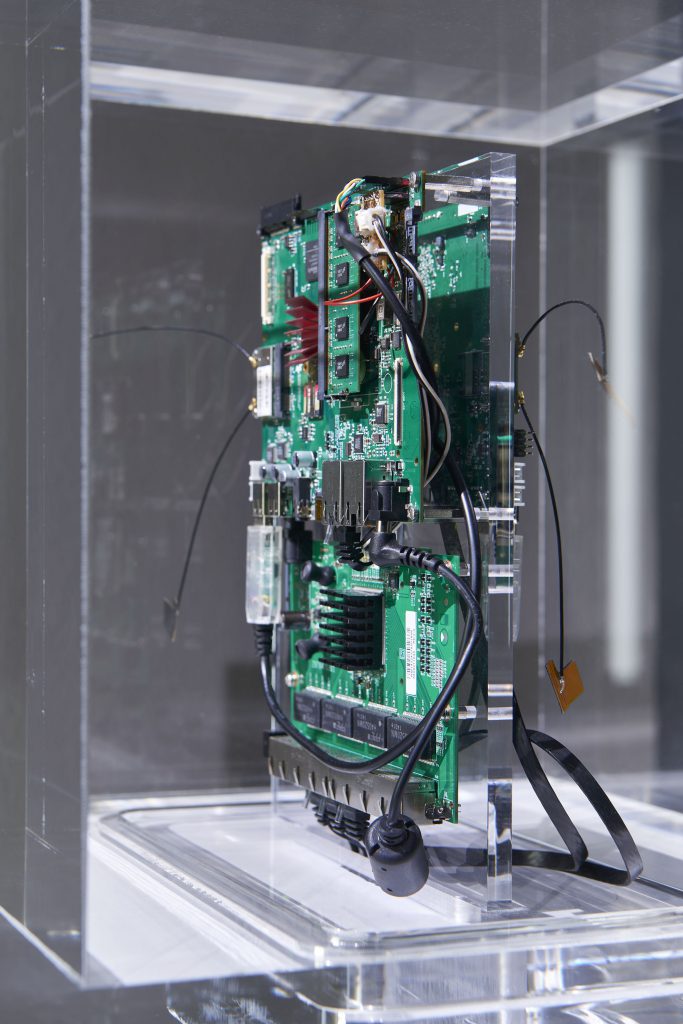

Farther into the exhibition,a piece by American artist and geographer Trevor Paglan, Autonomy Cube (2015), is visually what might be more typically expected to be on display in an Information Age exhibition. Within a transparent cube on a pedestal sits a mess of circuit boards and wires. The cube, though also an object to be viewed, is a working wi-fi hotspot for the duration of the exhibition, but one that utilizes Tor, an independent network of servers and relays that allows users to have their data anonymized. Particularly within the context of the gallery space, this wi-fi hotspot and object incites viewers to consider whom might use it; persecuted or oppressed journalists, artists, and others have been known to rely on these types of networks, however, so do criminals—the technology is neutral, its use is often not.

Minorities, 2018. Photo: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

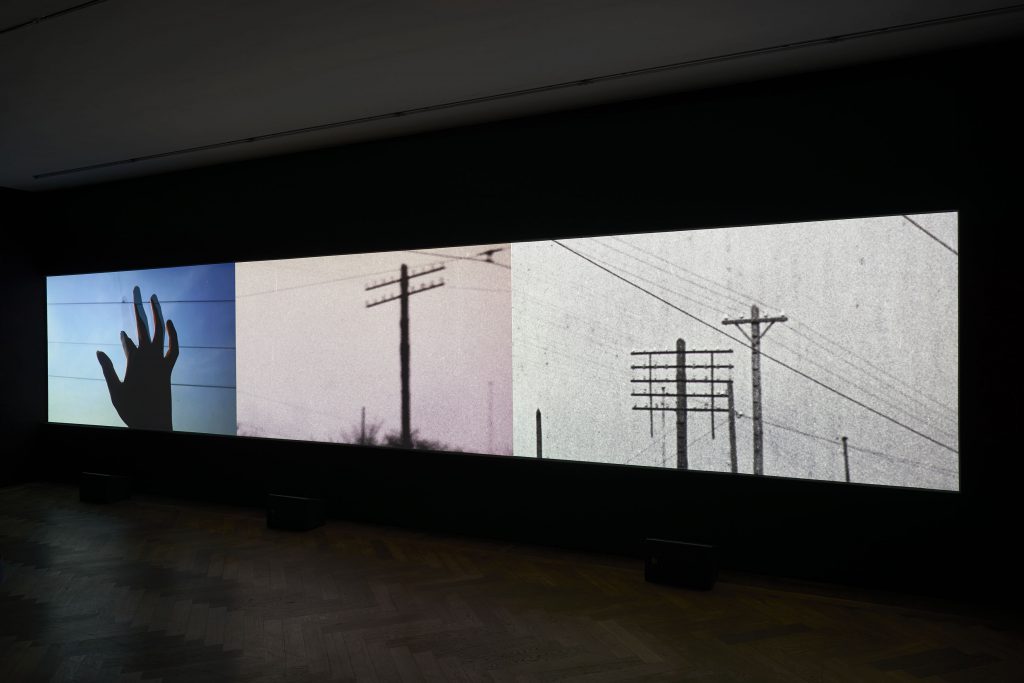

Continuing this thread is Chinese artist Liu Chang’s 40-minute, three-channel video Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities (2018). Using a combination of visually stunning, documentary style drone footage, kaleidoscope filters, and images from social media, the film is overlaid with voiceover in Muya, a language related to Tibetan, that speaks on a wide array of topics related to information and technology in China—from the introduction of the telegraph in the Qing dynasty to speculation on a future that holds interstellar communication. A large portion of the film also details the effect of crypto mining and blockchain technology on rural communities, specifically in western China. Currently, it is estimated that crypto mining accounts for upwards of 70% of the world’s computing power. Crypto mining requires a vast amount of energy and space to complete, which has led to miners building mining “farms” (warehouses filled with high-tech computer mining equipment) in remote regions to take advantage of the ambient low power usage as compared to major cities as well as well as available hydro-electric plants. This, of course, has impacted the communities of these regions in variety of ways, including draining local power reserves as well as exploiting workers to monitor these farms. The film covers a breadth of different subjects related to crypto currencies, and the extent of Liu’s own meticulous and thorough research is apparent.

Photos: Philipp Hänger / Kunsthalle Basel

Though not an official theme of the exhibition, a preoccupation with how various periods within the Information Age will be viewed retrospectively is also apparent through a number of the artists’ works. This theme is most evident in two works by American-born Simon Denny, Remainder 1 and Remainder 2 (both 2019). Each work is comprised of a Patagonia sleeping bag that has been adorned with scarves that belonged to Margaret Thatcher, which Denny purchased at auction. Oriented upright and elaborately decorated, they recall ancient Egyptian sarcophagi, which are laden with symbolism. Through the combination of Thatcher’s scarves and a piece of Patagonia, a brand intrinsically associated with tech companies in Silicon Valley, Denny draws a potent comparison between Thatcher’s neoliberal policies of the 1980s—which were notorious for their promotion of competition without consideration of individual privilege—directly with the tech and dot-com industries of today, which are often predatory and rife with class disparities.

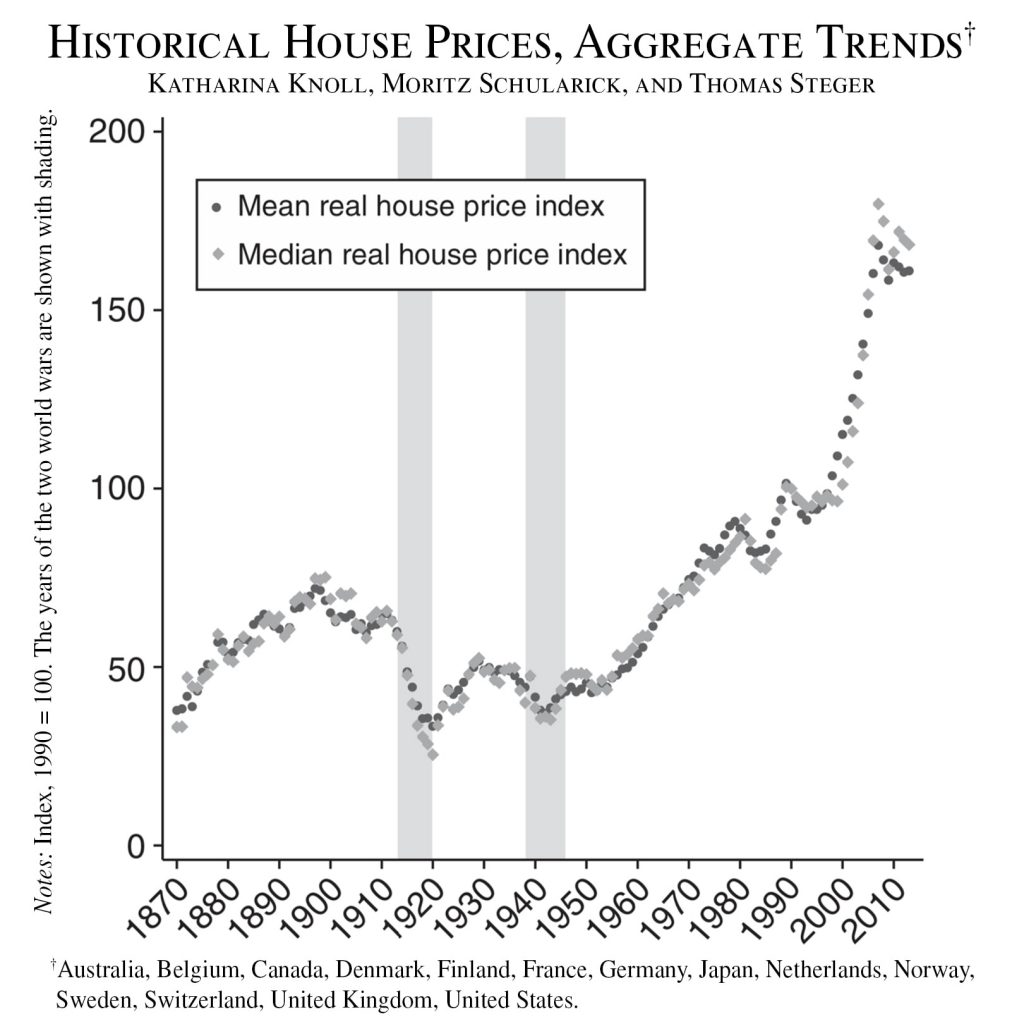

No Information Age exhibition would be complete without, of course, an NFT. Denny also contributed an NFT, viewable online through the exhibition’s website, Economist Chart NFT (with Moritz Schularick, Historical House Prices, Aggregate Trends) (2021). This NFT was created specifically for the show and was put up for auction in September through opensea.io—it ultimately sold for 4.41WETH, ≅ $13,500 at time of sale. The proceeds from the auction were split between the Kunsthalle Basel and the Canton Basel-Stadt, which not only provided monetary support for the museums, but also in effect served as a demonstration on how digital art and platforms can support both brick and mortar institutions as well as the state through taxes (this despite attempts by proponents of cryptocurrencies and NFTs to circumvent regulation).

Overall, the exhibition is a compelling, interrogative exploration of the many ways information and its dispersal can affect individuals and societies, and everything in between. It also presents an uncomfortable look at how information and technology can just as easily enhance or obliterate an individual’s—or even entire communities’—ability to raise themselves up, whether through knowledge, finances, or culturally. What is accomplished so seamlessly through this specific collection of the works presented within this exhibition is the posing of a question, framed through the consideration of time: How will the free and open circulation of information through advancing technology help or hinder our future? The exhibition offers a cautiously optimistic outlook. Though the free flow of information and technology have often been used nefariously, both are equally capable to be used (and have been) for good. Additionally, the accessibility of information now allows for the interrogation of how it is used, organized, and implemented, for changes and adjustments to better reflect an intersectional view of the world today, as well as how we choose to move into the future. “Information” is an unimaginably broad concept, and the understanding of how it affects us on a day-to-day basis as well as historically, and into the future is still in its nascency. The artists participating in INFORMATION (Today) are hyperaware of this phenomenon, and focus on vignettes of the big picture, so to speak—whether it is in the display of archaic catalogue labels featured in Swiss artist Alejandro Cesarco’s piece New York Public Library Picture Collection (Subject Headings) (2018), or in American Tobias Kaspar’s All-over logo (black) and Logotype (red rose) (both 2020), which draw sharp focus on capitalist logomania and the rise of self-branding. The mere acknowledgment of these specific facets of the Information Age is a signal that the situation can be changed by way of them being showcased in a concise and physical format, corporealizing what is often viewed as purely nonmaterial, like internet access.

Through the interpretation of the artists, INFORMATION (Today) is a snapshot of the Information Age as experienced today, but with an eye to the future. Viewed within the larger context that includes the MoMA’s exhibition of 1970, this show highlights how even over the course of just 50 years, data harvesting, its proliferation and distribution has changed dramatically, and without precedent. Even more prophetically, visitors are compelled to consider what the landscape of information will be 50 years from now.

INFORMATION (Today) is on view at Kunsthalle Basel through November 1, 2021. The show will travel to the Astrup Fearnley Museet, Oslo, January 27–May 1, 2022.