1. Tracey Emin at Galeria Lorcan O’Neill

In this particular moment of apprehension and anxiety in the midst of the coronavirus outbreak, the tumbling financial markets, and against the backdrop of climate change, not to mention the tension-fraught U.S. presidential election, Tracey Emin examines “how it feels.” Her beacon-like pink cursive neon sculpture hung high on a wall, implores frantic fair-goers to pause for a moment and ask themselves “How does it feel“? How does it feel to be alive on planet earth in 2020? For the once-controversial and now venerable British artist, the answer is both a public expression and a private existential dilemma that she further explores in the fluid, gestural self-portrait paintings also featured by this Rome-based gallery.

The Caddy Court (detail above), 1986-1987

mobile tableau: 1978 Cadillac with 1966 Dodge van, plaster casts, photographs, wood, metal, cloth, books, paint, polyester resin, light, shelves, curtain, antlers, animal skulls, taxidermy animal heads, clothing, furniture, clock, American flag,

microphones, pitcher, glasses, gavel /

84 x 276 1/2 x 100 in. (213.4 x 702.3 x 254 cm)

at L.A. Louver.

2. Edward & Nancy Kienholz at Pier 94’s Town Square/L.A. Louver.

Known for poetically grotesque sculptures and installations laden with acerbic, socio-political commentary, American artists Edward Kienholz (1927-1994) and partner Nancy Reddin Kienholz (1943-2019) created The Caddy Court (1986-1987) as a scathing critique of the U.S. Supreme Court. On view in the U.S. for the first time since 1997, the work alludes to the country’s early years, when the Supreme Court originally functioned as a roving circuit court. With a touch of biting humor, the artists present here a 1978 white Cadillac, which they gutted and filled with a small library of law books and a wood bench where nine seated figures, with taxidermied animal heads and skulls, and wearing formal robes, represent the justices. Viewers enter the car, one by one, through black curtains along the side, to confront the ghastly judges, alarming to behold and easy to conflate with the horrific potential of bias and imbalance that the current Supreme Court bears.

108 x 57 x 53 inches,

at David Nolan, New York.

3. Mel Kendrick at David Nolan

For decades, the Boston-born New York artist Mel Kendrick has been exploring the possibilities of abstract sculpture within a limited vocabulary of geometric shapes made of wood, or cast concrete for his sprawling outdoor installations. By now, those forms have become a veritable lexicon of totem-like compositions and architectonic constructions that are distinctly his own. A particularly large and impressive work Sculpture No. 4 (1991), made of cut and carved black wood, is one of the outstanding works at the Armory. Looming some nine feet tall, with gracefully clustered cubic forms dynamically balanced upon elongated leg-like extensions, it stands as a formidable sentinel.

painted bronze, iron, and painted wood

Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp.

4. Mark Manders at Zeno X Gallery

Dutch artist Mark Manders creates an uncanny verisimilitude in his bronze sculptures that resemble clay, in his reconstituted works on paper that recall newspapers, and in his elaborate installations that impart a sense of unease as well as urgency. The story remains perpetually elusive, as in a classic and characteristic work such as Working Table (2017). This resplendent composition consists of four large, nearly identical heads resting on a rectangular steel table. It might suggest an ancient Greco-Roman sculpture where it not for the vertical slivers of bronze painted a deep yellow cutting into the left eye and cheek of each head. With these startling elements, Manders alludes to the work of his compatriot Piet Mondrian and the tradition of De Stijl, Neoplasticism, and other modernist abstract movements from which Mander’s figurative art has evolved.

27 1/2 by 21 1/2 inches (70 x 55 cm)

at Dittrich & Schlechtriem Gallery, Berlin.

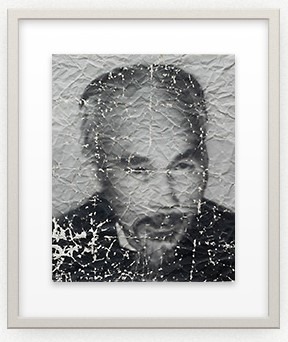

5. Gerhard Richter at Dittrich & Schlechtriem

One of The Armory’s Show’s perennial attractions is the inevitable element of surprise in encountering an unusual or unexpected work. This year, it’s Gerhard Richter’s Ho Chi Minh, a smallish painting with an outsize impact. Coinciding with Richter’s survey at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in step with today’s political tumult, this painting of 1971-71 was based on a crumpled newspaper photo of the North Vietnamese leader. It evokes the political ironies of the day. With the Vietnam War raging in the East and the counter-culture revolution underway in the West, the cacophonous upheavals of that time echo throughout the global conflicts of today.

featuring recent sculptures by Zhao Zhao (foreground)

and paintings by Adel Abdessemed.

6. Zhao Zhao and Adel Abdessemed at Tang Contemporary Art

Walking on the asphalt floor of this booth, one steps on a configuration of flattened metal pieces, rather like Carl Andre floor sculptures. These striking works by Chinese artist Zhao Zhao, however, are imaginatively based on images of roadkill–animal victims of hit-and-run drivers as seen along roads in China and certainly throughout the world. Some of these roadkill sculptures appear in the shape of maps of China, with individual provinces designated by the tones of various metals–copper, aluminum, brass, etc. Neatly corresponding to the sculptural works, large recent abstract paintings by the Algerian artist Adel Adbessemed appear to made of roadkill blood. In fact, he used a type of liquid that moviemakers use to simulate real blood on screen.

stop-motion animation

6 minutes, 36 seconds

Courtesy the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles.

7. Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg at Tanya Bonakdar

This year The Armory Show’s executive director Nicole Berry and deputy director Eliza Osborne led a team of curators to organize special projects for the fair, including Los Angeles curator Anne Ellegood, who oversaw “Brutal Truths,” the platform for the Kienholz installation, The Caddy Court (see above), as well as this terrific video and sculpture installation by Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg. The team’s quasi-surreal images in the stop-motion animation film are part of elaborate morality tales of love, lust, power and greed. The hybrid plant-animal sculptures are similarly ambiguous and enthralling.

hand-painted, mixed-media multiple in a variant edition of 7

wood, enamel, acrylic, digital photograph, glass, screenprint, and brass

72 x 72 x 1 1/2 inches

Durham Press, New York.

8. Leslie Wayne at Durham Press

Known for her intricate and highly textural trompe l’oeil paintings, Leslie Wayne introduced at The Armory Show her recently produced Here and Now, a multiple with unique variants. The work features a tall wood cabinet, with movable doors, packed with books, a radio and video cassettes. On the left side of the cabinet, a black background punctuated by stars suggests a cosmic dimension for a rather unassuming piece of furniture. This multiple, in an edition of seven, amounts to an exceptional feat of enhanced printmaking. It is also an example of an artist transforming a mundane household object into something extraordinary and almost otherworldly.

featuring Niyi Olagunju sculptures (foreground)

and Nkechi Ebubedike paintings (background).

9. Niyi Olagunju and Nkechi Ebubedike at Tefeta Gallery.

This engaging presentation featured the work of two artists of Nigerian descent. In his sculptures, Niyi Olagunju re-energizes the mythic power of shoulder masks from Guinea, creating highly stylized variations of the traditional forms. Coating the wooden shapes with gilded aluminum, Olagunju comments on the illicit trade in classical African ritual objects and art. The works correspond well with the richly hued, quasi-abstract figurative paintings by New York-based painter Nkechi Ebubedike. In her work, she explores notions of masking, veiling and taboo, and in the process touches upon conflicts of emotion and desire.

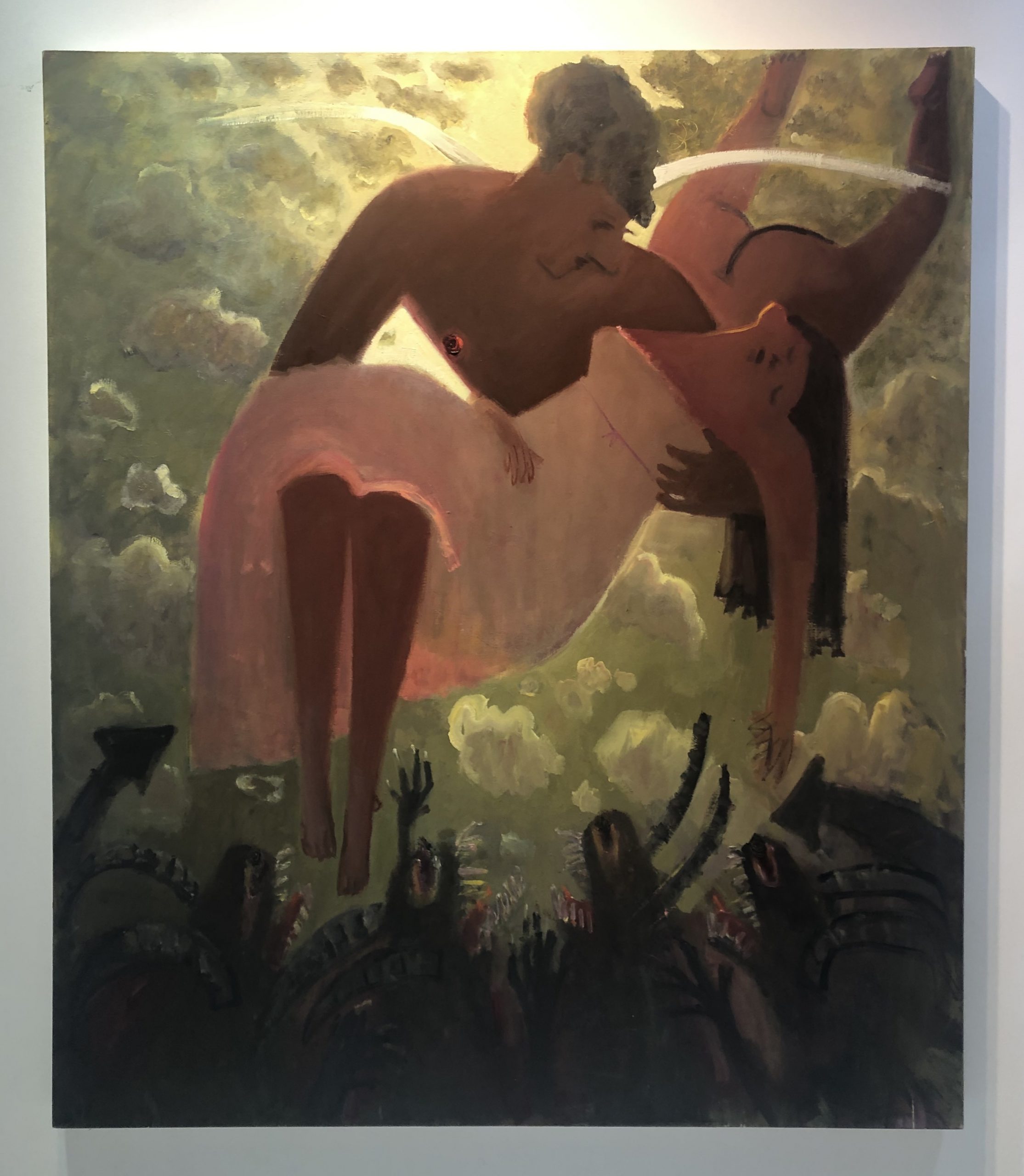

oil on canvas

68 by 58 inches

Zürcher Gallery Paris and New York.

10. Kyle Staver at Zürcher Gallery

Kyle Staver’s large paintings, reliefs sculptures and works on paper infuse the iconography of Greco-Roman mythology and Biblical stories with a contemporary relevance and meaning. Shown in conjunction with works by Matt Bollinger, Staver’s paintings on view here, with their exaggerated figures, deep shadows and bravura brushstrokes, appear to glow with a quiet luminescence. Hopelessly romantic images such as Guardian Angel (2018) are ultimately hopeful, and appear absolutely necessary today. In dire times like these, who wouldn’t want someone to watch over us, save us from catastrophe, oblivion, or just ask us how we feel?